Western Morning News

Big Medicine, Only Joy and The Alphabet Series: Mixed Media Works by Matthew Lanyon

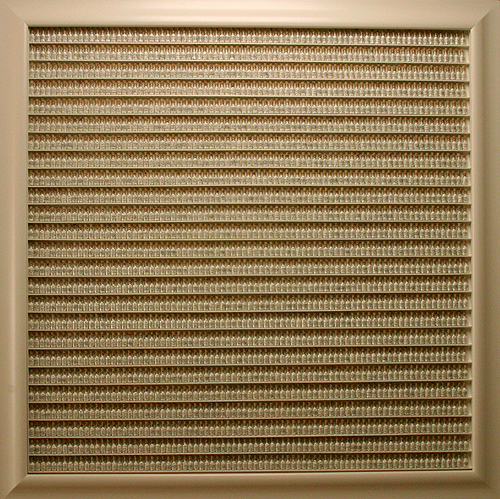

Big Medicine 2011

So these Bottles, homeopathic medicine bottles with handwritten labels containing fragments of language sifted from a life and a time then hung up like a painting: what are they about?

Matthew Lanyon is an artist born and based in St Ives, mainly now working in oils but back in 1996 he wrote a poem and illustrated it with images, some of found and manipulated objects. The poem, ‘Only Joy’ is about Time and The Creation and in the beginning was the Word – language, a foil to time and extinction, and language as remedy , which he says, it always is. Stories are continually retold and remade to give us hope and solace in this new world of facts, diagnoses, statistics and science. Lanyon says for a remedy to be efficacious it has to be veiled; then it can promise the earth. The God in the poem is a bit miffed at having lost his identity, his gender. In a later poem the male writer acknowledges his is a small offering against the vast female empire of time ‘her hours now his minutes win’. So there is a largely masculine, comedic, joyful source to what has become a series of works; some of which are undeniably frustrating and contradictory but ultimately empowering.

stand back while she catches the spider

One of the illustrations for the original poem was a small collection of 19thCentury homeopathic medicine bottles, filled or part filled with pills, picked up from a car boot sale. He later wrote a short ‘list’ poem describing elements of time in plurals and wrote it on the bottle labels beginning with fine mornings and ending with yesterdays.

numbered edition (ten available).jpg)

Only Joy

numbered edition (unique)

A framed version of it is now available in a numbered series of uniques as ‘Only Joy’, an intimate work holding great tyrannical tracts of time such as aeons in a small frame alongside personal but also collective cultural experiences, months of sundays for example. It has at once a curiously consoling effect , as well as pitching us into the deep space of our vast infinite non existence. The only other piece in the series where the labels have homogeneity is ‘80 Ways to Make her Happy’, a newer collaborative work featuring labels with affirmative, permissive, and gentle commands, apparently celebrating elements in a relationship, as in let her cut your hair and insist on talking about difficult things.

write me few short lines she said

Lanyon went on to develop form and content over a number of years under the title The Alphabet Series, a reference to the invention of the Alphabet in the story of Cadmus and Harmony from Greek mythology , but they have rarely been shown. With each work it seems he cannot be sure if that is the end of it or a new beginning. His latest piece is a case in point: ‘Big Medicine’ is possibly the ultimate development using over 2,000 glass vials imported all the way from China. Their handwritten labels in his own tiny handwriting suggest jewellery etched or sculpted on the wall with all the visual power of multiples and all the draw of the unique, as almost all the labels create a different burst of language.

For some time Lanyon worked on the basis of creating labels which read as if they could be taken as pharmaceutical remedies, in plurals, so for example having two walks on the wild side , or taking a day’s supply of tough cookies, and although it may not cure your cancer or solve your unemployment issue, it makes you feel good. But eventually he abandoned pluralising and began to use a whole variety of forms including dialogue, without a character, and long pieces which strayed across three bottles occasionally; all rules eventually broken.

you should have gone and got a cup…

The pieces are nostalgic, as anything must be which refers to a canon of literature and culture collected over a lifetime of delight in language equally at home with classical references alongside comic catch phrases and irreverent expletives in use, or just out of use, today . The bottles themselves, beautifully proportioned, corked and handwritten, seem also to pay respect to the ancient arts as if these really can offer something distilled and enduring , as in perhaps the one that promises

better ancestors.

The labels take up fragments from things heard, overheard, written, read, imagined, transcribed, and transcend authorship. As a reader one is likely to look for sequencing and meaning and sometimes, take pleasure in finding it; but often it can’t be traced, so instead there is a challenge to engage with diversity, to tolerate gaps. Of each label : Do we recognise the source? Is it Lanyon’s own writing? Did someone really say this to him in an intimate situation? Or is it a well known line he can’t stop repeating aloud? Does it make us smile? –and yes, often as not. But then eventually in the bigger pieces we might tire, come up for air, wish for a large magnifying glass, dream of where we could hang the piece to give the greatest possible extension of good, - a solicitor’s office, a hospital, a railway station, waiting room, somewhere people can return to it, look for their favourites and fail to find them, finding some other jewel instead.

I’m out

Lanyon says that his preferred medium is a kind of low earth orbit. He imagines a single space where the fusion of word and visual art can evolve like microbes without gravity or the civilising geometry of form. By making these works at times almost illegible but in a frame on a wall he says it’s like pretending it’s as accessible as a painting in one hit, but it is quite different. For me the pieces create an interesting public/private threshold: there is an opportunity for intimacy with the reader ; one can’t pretend not to be reading it or to be casually reading as one could with a poster or advert at a distance; it is a one to one encounter, earnest, playful, exposing, delivering perhaps the mysterious undetectable homeopathic hair of the dog to the self healing organism, or the love heart to the sweet tooth, but right out there in a public space on public view...

it’s collage Jim, but not as we know it

Judith Hodgkinson 4th Sept 2011

|