REVIEWS '09

A LIFE LIVED BACKWARDS Alex Wade, September 2009 issue of Cornwall Today

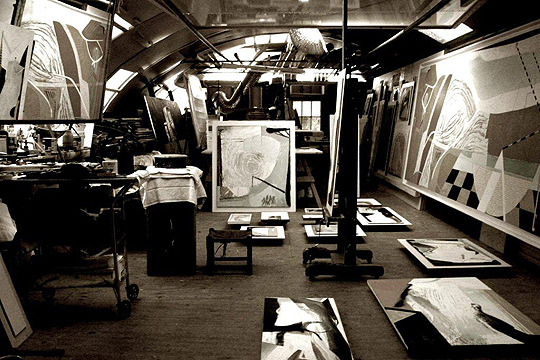

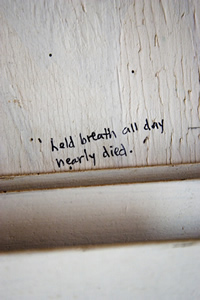

“The best thing about being a son of is that it might raise the stakes a bit. You've got to raise “After university, I went travelling for about four years and then, upon returning to Britain , trained as a carpenter and joiner,” says Lanyon, a tall, sturdily built man with quintessentially Celtic black curly hair. He immersed himself in work in the building trade for a decade, specialising in house restoration in Cornwall , the county of his birth and upbringing, and Leicester , where he attended university. Lanyon – whose measured sentences are every bit those of the intellectual – admits that there was a degree of dissonance between his education and early career. “This was the mid-Seventies, a time when the disassembly of classical training began,” he says. Today, though, merely a cursory glance at Lanyon's work reveals that he was never destined for Lanyon's oeuvre is abstract art of the highest order, but it is difficult not to conclude that rebellion has consistently been crucial to its genesis. He is, indeed, a curious mixture, shy and introverted and yet remarkably open about a cataclysmic event in his life – the death of his father when he was 13. Peter Lanyon died in 1964 in a gliding accident; Lanyon has written that “His death came into me like an ocean.” Speaking in the workshop the uses as a studio in the garden of his West Penwith home, Lanyon sheds light on a problem faced by few but no less compelling for its comparative rarity – what it's like to be the son of a famous father.

“There were six of us,” he says, “and we grew up in an environment in which the movers and shakers of the art world were passing the sugar and spreading the cream.” But though Peter Lanyon knew everyone who was anyone from the zeitgeist of 1960s abstraction – his mentors were Naum Gabo and Ben Nicholson – his offspring weren't really aware of his status until later in their lives. ”We never thought of Dad as a famous artist,” says Lanyon. “We got on with drawing and painting, because that's what we did as children, but never with much thought of its significance.” With his father's death, Lanyon consciously sought a different path than the artistic one. “I won the art prize at ‘O' level but deliberately set out to study something different. I studied science instead.” His teenage academic preoccupations led to a place at Leicester University , where he took a degree in Combined Sciences, and then came the lengthy stint in the building trade. Was this a deliberate attempt to escape his father's legacy, one that seemed more of a burden than a blessing? “Definitely,” is Lanyon's immediate, unequivocal response. Now, though, Lanyon is in the first year of his third decade as a professional artist. He is highly acclaimed and utterly absorbed in the process and act of artistic creation. He will get up at 3.00 a.m. to observe sunrises and thinks nothing of working 11 hour days. Aside from gardening and reading – he cites the Italian writer Roberto Calasso's The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony as an inspiration, and is also partial to the great Russian émigré Vladimir Nabokov, not to mention Samuel Beckett and Greek mythology – he does little other than work on his art. How, then, did things turn around so much? How, in short, did he come to painting? “Sometimes, a rock has to move out of the way before a thing can happen,” says Lanyon. “In my late 30s something shifted. I was fortunate, because I'd made some money in the building trade, so I was able to start on my painting with some degree of security.” By then Lanyon was married to Suzanne – who died two years ago – and the couple had a young son, Arthur. The family had settled in the West Penwith home in which Lanyon still resides. Lanyon painted because “I realised that you could have a sickness that can't be diagnosed. I understood that not painting was making me sick.” But his embrace of art did not entail self-promotion. Indeed, although many artists are ill at ease with the world of commerce, Lanyon comes across as one of the most avowedly non-commercial there is. Eventually, though, a friend's insistence led to the beginning of a relationship with Martin Val Baker's Rainy Day Gallery. Lanyon's September show is Val Baker's 200th . As well as the huge White Horse painting, it will feature fresh takes on Porthleven, Godrevy, Porthgwarra, Nanjizal and other landscapes in Cornwall, a county which Lanyon describes as “a tremendous opportunity – it's everywhere – Cornish granite has even found its way to India”.

|

|

||