I was

born in St Ives, Cornwall in 1951, one of six. My father was Peter

Lanyon - a landscape painter who became a major figure in the world

of art.

After

the war St Ives had become a centre of the modern movement in abstract

art and my father was commissioned to produce the painting Porthleven for The Festival of Britain. His mentors were Naum Gabo and

Ben Nicholson. While I was tearing round the garden as Davy Crockett,

movers and shakers of art were passing the sugar and spreading the

cream.

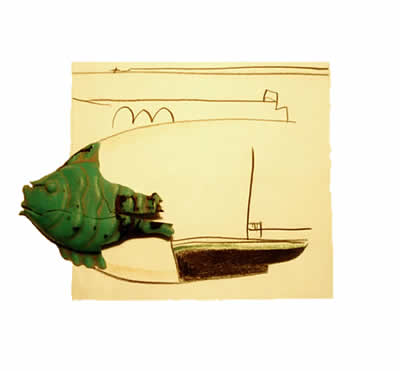

Little

Park Owles 1963

Shortly

before he died in 1964, as the result of a gliding accident,

we spent some days together in his studio making a model aircraft.

We made prototype wings out of polystyrene and tried to strengthen

them with muslin and glue-size. Years later I read what someone

had written about his painting Clevedon Night, which

had these two prototype wings attached to the canvas. They might

be 'boats bobbing up and down' but I knew what they were. They

weren't boats. But it doesn't matter whether this was true or

not. That isn't the point - we read our own life into paintings.

A

few days with him in the studio, a few days camping out in the

Thames van on Perranporth Airfield and he was gone. I was thirteen.

He was forty-six. His death came into me like an ocean.

North

Cliffs 1968 (photo - Paul Otto)

I

was brought back from Bryanston to the local grammar school

in Penzance. I won the art prize and thought about going on

to art school but my mother said, 'You'll end up in a corner

screaming.' This was the 1960's. In the 30's she'd had to do

three years of drawing before they'd let her hold a brush. So

that was that. It would be twenty-five years before I got the

smell of paint again. I went on to university and joined the

meritocracy - the beginning of the great unwinding of the class

system. It was exciting. There was a political edge - we were

on the streets.

Half

a century later, I look back in wonder:

Upper class background, middle class education, university career

in free-fall - I should have been a class disaster. The one

saving grace in messing up is you get a new beginning. If you

can realise that and shoulder the weight of having taken goodwill

from others and shagged it you get a new beginning.

It

was a terrible trade off but I got so much from four years at

university starting with Geology and Psychology. In my last

year I read History of Science, Archaeology and Linguistics.

I was a burning fuse - changing courses and reading stuff that

wasn't part of the brief. I was after something.

Four

years in academia then a job on a tractor - working in the building

trade, becoming physical. The tragedy and sadness of my loss

was bearable. I trained as a carpenter and joiner. I handled

many diverse materials - renovating four houses, subcontracting

and working for other builders. I just learned so much.

Little

Park Owles '92

|

|

It

was not until 1988 that I began to take my artwork seriously.

At that time I was drawing and painting every morning with my

son, in the days before he went to school. He always had the

best titles. I'd ask him about one of his drawings and he'd

say with the absolute sincerity of a four-year-old, 'Three

Cows Walking on the Water'.

Between my father and my son I had begun to address the problem

of what anything is, or is meant to be in a painting. If cows

could walk on water and bits of polystyrene that were once wings

can bob up and down like boats, then painting is alive and the

better for being marginalised by all the exquisite distractions

of sound and movement. |