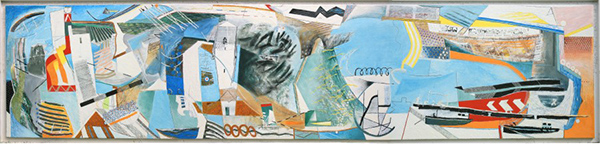

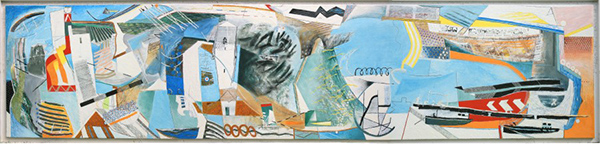

The Listening Sea

22 feet by five oil on canvas

In January of this year, I received an email from Matthew Lanyon inviting me to write something about his work. I knew neither him nor the work, but when he described how he went in to purdah for a year or so to produce a single big painting, and how the current one measured 22 feet by 5, I wrote back at once: I could visit him in early February.

His reply came arranged in short lines, giving it the appearance and rhythm of free verse:

thanks your swift

february fine

map attached.

The attachment was headed ‘fairly useful map’, and as I squinted to read the scanned image, I found myself pulled into a hand-drawn odyssey around the hinterland between St Ives and Penzance. The coast was an exuberant freehand frame and each little track and road was marked either ‘yes’ or ‘no’, as if they were choices on a Bunyanesque adventure. This was Matthew Lanyon country.

In the end I had to postpone the February meeting but that only meant a prolonging of his wonderful emails - dry pithy declarations and brief narratives, glimpses of the wide-ranging world he inhabits and from where his work comes. In one he told the story of how, years ago, he’d bought a great batch of binder twine at a farm sale, but then couldn’t work out what to do with it:

‘I wrote to NASA with a project to

take a roll of the stuff up in space

have an astronaut chuck it out the back door

remembering, like I don’t mostly

to tie the end off, imagine ariadne’d…

now, each of these rolls is about

two thousand feet long and

according to newton

one will go on unravelling, after a suitable shove

in one long beautiful straight line

out in space until it gets to

the end of its end of

its end’

NASA thanked him, he said, and told him they’d keep the idea on file ‘just in case’.

So on a damp March day, I printed out the ‘fairly useful map’ and drove west, crawling through the mist of west Penwith to the end of the end lane. Matthew was there in his granite cottage, his face full of smiles and good humour, and topped by an impressive set of curls. He was wearing a blue boiler suit lined with red quilt. He had the large hands and physique of a man built to forge something new from the world’s raw materials.

Until he took up painting in the late 1980s, Lanyon had worked in the building trade and as we walked through a lean-to at the back of the cottage, we passed benches full of tools and materials. In the roof was a stack of 9x3 Douglas fir for making frames.

The garden itself was a collection of clapboard sheds and workshops. Each was a cluttered showcase of his years as an artist - as if once he’d exhausted the capacity of one, he moved on to start filling the next. In the first were examples of a series of works from a few years ago when he took dozens of tiny homoeopathic remedy bottles, filled them with placebos and wrote on their labels snatches of thought and overheard conversation: ‘better ancestors’ or ‘It’s collage Jim, but not as we know it’ or simply ‘I’m out’.

In the next shed were some of his larger paintings laid out flat on a specially built platform. Climbing a set of step-ladders, I gazed down on Spiral Form. Matthew explained the image, calling out from across the room. It was based on a small drawing of his father’s, from which Matthew had constructed a geometric image of west Penwith and the alignment of Mount’s Bay with the rising sun. Gingerly I reached the top step and took in the bird-s eye view.

‘I love ladders,’ shouted Matthew. ‘My accountant asked me why I needed to buy eight ladders in one year. To look at paintings, I told him.’

And so to the last studio and The Listening Sea, this year’s mega-painting. It was fixed to one wall, seven yards of image in his crisp, trademark palette and semi-abstract swirl of shapes and textures. Striding along it, standing back, going in close to read his notes scribbled around its edge, a web of narrative began to emerge – of the ‘gentry coming down the line’ to St Ives station, a ‘bull reading text’, ‘Trencrom Hill in the snow’ and a woman in the tower of Godrevy lighthouse holding one end of a hammock.

Pervading them all were the particularities of west Cornwall and the experience of it – the Camborne-Redruth by-pass at night (a series of red dots of brake lights strung ogham-like along a line) or ‘sunrise over Godolphin on 22 February’ or simply ‘Perranporth airfield’ – Perranporth, where Matthew’s father Peter learned to fly gliders, a pursuit that led to his sudden death when Matthew was just thirteen.

The painting had been an exhausting process, and beside the great animate expanse of canvas, Matthew himself looked diminished. It was as if something of his vigour had been transferred to the painting.

Outside the mist had set in more closely, a formless mantle of greyish-white that had been gently coaxing the garden away from the fixed earth as we stood in the studio. Crossing the ground at our feet was a row of cat’s eyes, as if we stood on a length of abandoned road. Matthew rediscovered his energy in explaining them – picking out an alignment of the sun’s rising over Trencrom Hill on the summer solstice.

‘There – and there.’ He chopped the air precisely, swivelling through one hundred and eighty degrees. ‘North-east and south-west.’

And his large maker’s hand was suspended there for a moment, a cutting-tool powered by the great whirring engine of his thought, a blade pointing out into the blank ambiguity of the mist.

Philip Marsden. July 2015

|